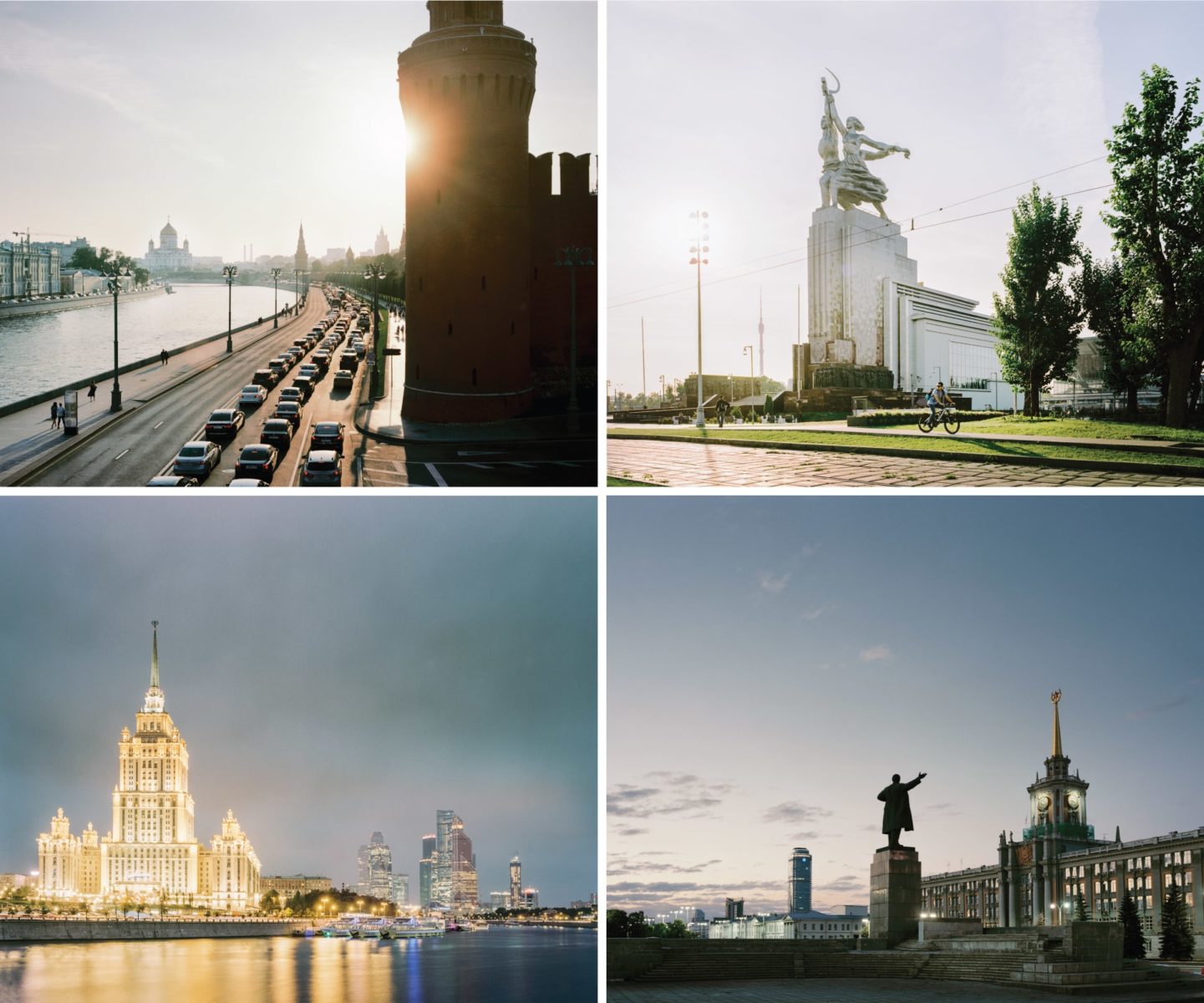

Alexander Gronsky

Canceled exhibitions of Russian artists trigger self-loathing, anxiety

- Photography by Alexander Gronsky

Three days after the Russian army invaded Ukraine, a 42-year-old Russian landscape photographer named Alexander Gronsky was arrested on a bridge just in front of the Kremlin in the center of Moscow for shouting “No to war!” with a dozen other protesters.

As he looked at the sun setting behind the Kremlin walls from a police van, thousands of miles to the west, a prestigious Italian photo exhibition of Gronsky’s work was canceled. “There is a time to firmly affirm the right of peoples to live in peace and a time to open up to dialogue and confrontation, without violence and death being invited to the table,” the exhibition’s curators announced.

Like many Russians opposed to the current regime, Gronsky has found himself in an increasingly worrying situation. Outside Russia, businesses and media organizations have stampeded out of the country, halting operations and imports to Russia. The ruble has been crashing. International flights are canceled and visa centers have closed their doors. Inside Russia, the regime has banned words like “war” and “invasion,” censoring the remaining media and intensifying its propaganda campaigns.

Gronsky spoke about art and disinformation in a time of war and the reasons he’s staying put in Russia for now in a conversation that has been edited for length and clarity.

When the exhibit was canceled you said that you were devastated to see art take the blow in this way, but that you understood the motivations behind it.

As a Russian person I feel powerless, ashamed and furious about everything that’s going on. I cannot influence it in any way and I perfectly understand that blame as a result will be put on everything Russian: Russian culture, Russian language and that in the nearest hundred years people will not make films about Nazis, but about awful Russians. Overnight, from being strange, mysterious, aggressive, foolish people we turned into monsters and we will not be able to wash this blame off for a very long time, it’s terrible. I am afraid that my son will hide the fact that he is half Russian when he grows up.

How is your work now received abroad?

I have to say I get a huge amount of support from Italy. I get 10 to 15 emails a day with just words of support. I had a group exhibition, a collaboration between the Reggio Emilia region and the Hermitage museum in St. Petersburg. It was canceled not because I was Russian, but because all collaborations with Russian state institutions were canceled. But I recently got an email from Reggio Emilia inviting me to the festival as a private artist. I don’t think I can go now. It’s really important to distinguish between Russian aggression, the Russian state, Russian artists, and Russian culture.

Meanwhile back at home there is huge pressure, censorship, and mass detentions of protesters — which have included you.

It’s not the first time I’ve been detained at a rally, but it’s nasty. When I showed up, I shouted out “No to war!” I was immediately grabbed by my arms and legs, and dragged. I still have this big scratch on my face. I was held for 12 hours at the police station. On March 16 there will be a trial and I will most likely be given a rather large fine.

There’s this feeling of powerlessness. It’s clear that I haven’t changed anything [in Russia] but it’s impossible not to go out. There are no other options at all. I can’t vote, I can’t sign a petition. I have to physically present my body as someone who disagrees because all elections and all polls are rigged. And in order to be seen at least in some way, you have to let your body be beaten, which is humiliating, but there is no other option in Russia today.

There is another issue that many Russians opposed to the regime face, which is dealing with their relatives who are pro-Putin and pro-war. This is the case in your own family.

My mom thinks I’m a traitor. It’s not a joke. It’s not an argument like between someone who likes tea and someone who likes coffee. It’s a huge shock to her, despite that for the last 10 years we were more or less aware of the fact that we have different views. I understood that she watches Russian television. She understood that I supported the opposition and we avoided talking about it, but now of course the war has exacerbated it so much that it is a very sharp conflict between us, with tears, with curses. Now everyone understands how serious and catastrophic the situation is. But people who watch Russian TV have this idea that while this is all terrible, we have no other choice. We will fight the whole world, to the last man, but the truth is on our side. The other half of the Russian population have a feeling that we are involved in a heinous crime and will be paying for it all our lives. Our children will be paying the price.

Do you try to make her change her mind?

It’s very difficult, it’s such a radical, intransigent position and they have so much rage. The version of events that the state media offers is constructed so that it’s not just a version of events, but a complete picture of the world in which everything is explained very clearly. This perfect structure of “the whole world is against us” finds fertile ground in Russia. People believe that we are fighting an evil fascist force, although in fact we are the fascist state that is trying to invade other countries. The amazing thing is that this cheap, talentless construction that’s being imposed on everyone — it works, it is amazingly effective. It’s a nightmare, how effective this brainwashing is.

Many are urgently leaving Russia. What about you?

I do not plan to flee the country yet. I’m in an advantageous situation, I have little to lose. My parents are in Estonia and they support Putin, but my son is in Latvia. If my child lived in Russia I would have run away a long time ago. I am worried that some of the posts that I wrote on Facebook in support of Ukraine have now become a criminal offense in Russia, but I still decide not to delete them. I don’t know, I’m scared but I can’t keep quiet either.

It’s scary. When I was a kid we were told a lot about World War II and the Nazi occupation. I often thought about what I would do if I lived at that time and the Nazis invaded and occupied, how I would resist. And now some of those childhood fantasies are coming back again. I just never imagined that I would end up on the fascist side instead of the occupied side. I can’t even imagine what’s going on and how to put it all together and create a coherent image of the world that I can live in.

No one is bombed in Moscow. Life in general is almost the same as it was a month ago. This is also a shock because I know of the nightmare happening in Ukraine, but my home is fine, the street is fine, the shop offers the same goods, maybe some prices have risen, but there is no sign of a nightmare.

And I see that most people live with the version that this war is some foreign policy nonsense somewhere far away. People honestly believe that after a couple of days everything will go back to normal; it’s just some political games. And at the same time there is a feeling that I am inside a cartoon because I’ve never seen such grotesque evil, such obvious grotesque evil. There’s always been shades of gray everywhere, everything was so complicated and suddenly, for the first time in my life, everything is simple. There is absolute evil that cannot be justified in any way. But I don’t know how much strength I have in me, how far I am willing to go in resisting it. I am human after all.

The story you just read is a small piece of a complex and an ever-changing storyline that Coda covers relentlessly and with singular focus. But we can’t do it without your help. Show your support for journalism that stays on the story by becoming a member today. Coda Story is a 501(c)3 U.S. non-profit. Your contribution to Coda Story is tax deductible.