When your body becomes the border

- By Erica Hellerstein

- Illustrations by Derek Abella

- feature

By the time Kat set foot in the safe house in Reynosa, she had already escaped death’s grip twice.

The first time was in her native Honduras. A criminal gang had gone after Kat’s grandfather and killed him. Then they came for her cousin. Fearful that she would be next, Kat decided she needed to get out of the country. She and her 6-year-old son left Honduras and began the trek north to the United States, where she hoped they could find a safer life.

It was January 2023 when the two made it to the Mexican border city of Reynosa. They were exhausted but alive, free from the shadow of the fatal threats bearing down on their family in Honduras.

The Big Idea: Shifting Borders

Borders are liminal, notional spaces made more unstable by unparalleled migration, geopolitical ambition and the use of technology to transcend and, conversely, reinforce borders. Perhaps the most urgent contemporary question is how we now imagine and conceptualize boundaries. And, as a result, how we think about community.

In this special issue are stories of postcolonial maps, of dissidents tracked in places of refuge, of migrants whose bodies become the borderline, and of frontier management outsourced by rich countries to much poorer ones.

But within weeks of their arrival, a cartel active in the area kidnapped Kat and her son. This is not uncommon in Reynosa, one of Mexico’s most violent cities, where criminal groups routinely abduct vulnerable migrants like Kat so they can extort their relatives for cash. Priscilla Orta, a lawyer who worked on Kat’s case and shared her story with me, explained that newly-arrived migrants along the border have a “look.” “Like you don’t know where you are” is how she put it. Criminals regularly prey upon these dazed newcomers.

When Kat’s kidnappers found out that she had no relatives in the U.S. that they could shake down for cash, the cartel held her and her son captive for weeks. Kat was sexually assaulted multiple times during that period.

“From what we understand, the cartel was willing to kill her but basically took pity because of her son,” Orta told me. The kidnappers finally threw them out and ordered them to leave the area. Eventually, the two found their way to a shelter in Reynosa, where they were connected with Orta and her colleagues, who help asylum seekers through the nonprofit legal aid organization Lawyers for Good Government. Orta’s team wanted to get Kat and her son into the U.S. as quickly as possible so they could apply for asylum from inside the country. It was too risky for them to stay in Reynosa, vulnerable and exposed.

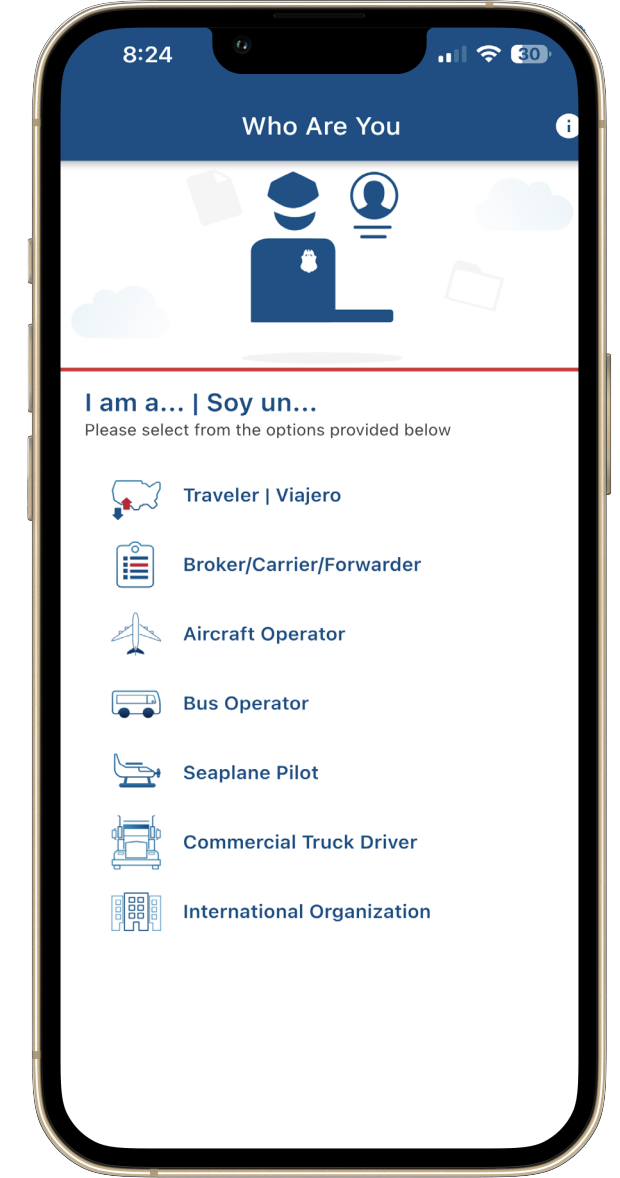

For more than a month, Kat tried, and failed, to get across the border using the pathway offered to asylum seekers by the U.S. government. She was blocked by a wall — but not the kind we have come to expect in the polarized era of American border politics. The barrier blocking Kat’s entry to the U.S. was no more visible from Reynosa than it was from any other port of entry. It was a digital wall.

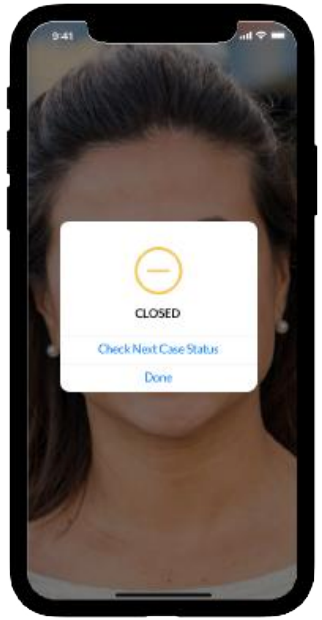

Kat’s arrival at the border coincided with a new policy implemented by the Biden administration that requires migrants to officially request asylum appointments at the border using a smartphone app called CBP One. For weeks, Kat tried to schedule a meeting with an asylum officer on the app, as the U.S. government required, but she couldn’t do it. Every time she tried to book an appointment, the app would freeze, log her out or crash. By the time she got back into CBP One and tried again, the limited number of daily appointment slots were all filled up. Orta and her team relayed the urgency of Kat’s case to border officials at the nearest port of entry, telling them that Kat had been kidnapped and sexually assaulted and was alone in Reynosa with her child. The officers told them they needed to use CBP One.

“It was absolutely stunning,” Orta recalled. “What we learned was that they want everybody, regardless of what’s happening, to go through an app that doesn’t work.”

And so Kat and her son waited in Reynosa, thwarted by the government’s impenetrable digital wall.

The southern border of the U.S. is home to an expansive matrix of surveillance towers, drones, cameras and sensors. But this digital monitoring regime stretches far beyond the physical border. Under a program known as “Alternatives to Detention,” U.S. immigration authorities use mobile apps and so-called “smart technologies” to monitor migrants and asylum seekers who are awaiting their immigration hearings in the U.S., instead of confining them in immigrant detention centers. And now there’s CBP One, an error-prone smartphone app that people who flee life-threatening violence must contend with if they want a chance at finding physical safety in the U.S.

These tools are a cornerstone of U.S. President Joe Biden’s approach to immigration. Instead of strengthening the border wall that served as the rhetorical centerpiece of former President Donald Trump’s presidential run, the Biden administration has invested in technology to get the job done, championing high-tech tools that officials say bring more humanity and efficiency to immigration enforcement than their physical counterparts — walls and jail cells.

But with technology taking the place of physical barriers and border patrol officers, people crossing into the U.S. are subjected to surveillance well beyond the border’s physical range. Migrants encounter the U.S. government’s border controls before they even arrive at the threshold between the U.S. and Mexico. The border comes to them as they wait in Mexican cities to submit their facial recognition data to the U.S. government through CBP One. It then follows them after they cross over. Across the U.S., immigration authorities track them through Alternatives to Detention’s suite of electronic monitoring tools — GPS-enabled ankle monitors, voice recognition technology and a mobile app called SmartLINK that uses facial recognition software and geolocation for check-ins.

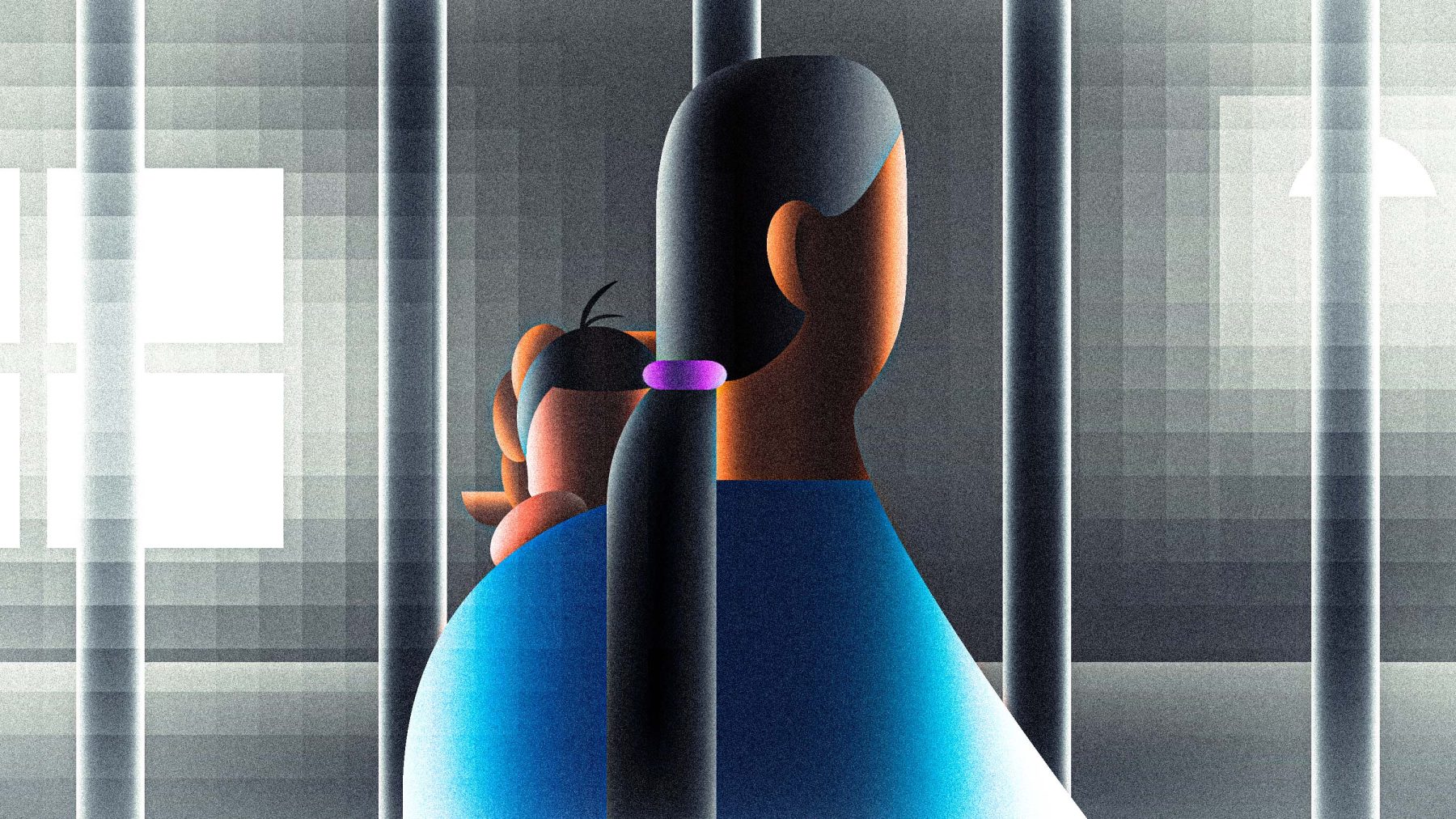

Once in the U.S., migrants enrolled in Alternatives to Detention’s e-monitoring program say they still feel enveloped by the carceral state: They may be out in the world and free to walk down the street, but immigration authorities are ever-present through this web of monitoring technologies.

The program’s surveillance tools create a “temporal experience of indefinite detention,” said Carolina Sanchez Boe, an anthropologist and sociologist at Aarhus University in Denmark, who has spent years interviewing migrants in the U.S. living under Alternatives to Detention’s monitoring regime.

“If you’re in a detention center, the walls are sort of outside of you, and you can fight against them,” she explained. But for those under electronic surveillance, the walls of a detention center reproduce themselves through technology that is heavily intertwined with migrants’ physical bodies. Immigration authorities are ever-present in the form of a bulky monitoring device strapped to one’s ankle or a smartphone app that demands you take a selfie and upload it at a certain time of day. People enrolled in Alternatives to Detention must keep these technologies charged and fully functioning in order to check in with their supervisors. For some, this dynamic transfers the role of an immigration officer onto migrants themselves. Migrants become a subject of state-sanctioned surveillance — as well as their own enforcers of it.

One person enrolled in Alternatives to Detention told Sanchez Boe that the program’s electronic monitoring tools moved the bars of a prison cell inside his head. “They become their own border guard, their own jailer,” Sanchez Boe explained. “When you’re on monitoring, there’s this really odd shift in the way you experience a border,” she added. “It’s like you yourself are upholding it.”

As the U.S. government transposes immigration enforcement to technology, it is causing the border to seep into the most intimate spheres of migrants’ lives. It has imprinted itself onto their bodies and minds.

The app that Kat spent weeks agonizing over is poised to play an increasingly important role in the lives of asylum seekers on America’s southern border.

Most asylum requests have been on hold since 2020 under Title 42, a public health emergency policy that authorized U.S. officials to turn away most asylum seekers at the border due to the Covid-19 pandemic. In January 2023, the same month that Kat arrived in Reynosa, the Biden administration implemented a new system for vulnerable migrants seeking humanitarian exemptions from Title 42. The government directed people like Kat to use CBP One to schedule their asylum appointments with border officials before crossing into the U.S.

But CBP One wasn’t built for this at all — it debuted in 2020 as a tool for scheduling cargo inspections, for companies and people bringing goods across the border. The decision to use it for asylum seekers was a techno-optimistic hack intended to reduce the messy realities at the border in the late stages of the pandemic.

But what started out as a quick fix has now become the primary entry point into America’s asylum system. When Title 42 expired last month, officials announced a new policy: Migrants on the Mexico side of the border hoping to apply for asylum must now make their appointments through CBP One. This new system has effectively oriented the first — and for many, the most urgent — stage of the asylum process around a smartphone app.

The government’s CBP One policy means that migrants must have a smartphone, a stable internet connection and the digital skills to actually download the app and make the appointment. Applicants must also be literate and able to read in English, Spanish or Haitian Creole, the only languages the app offers.

The government’s decision to make CBP One a mandatory part of the process has changed the nature of the country’s asylum system by placing significant technological barriers between some of the world’s most vulnerable people and the prospect of physical safety.

Organizations like Amnesty International argue that requiring asylum seekers to use CBP One violates the very principle upon which the U.S. asylum laws were established: ensuring that people eligible for protection are not turned away from the country and sent back to their deaths. Under U.S. law, people who present themselves to immigration authorities on U.S. soil have a legal right to ask for asylum before being deported. But with CPB One standing in their way, they must first get an appointment before they can cross over to U.S. soil and make their case.

Adding a mandatory app to this process, Amnesty says, “is a clear violation of international human rights law.” The organization argues that the U.S. is failing to uphold its obligations to people who may be eligible for asylum but are unable to apply because they do not have a smartphone or cannot speak one of the three languages available on the app.

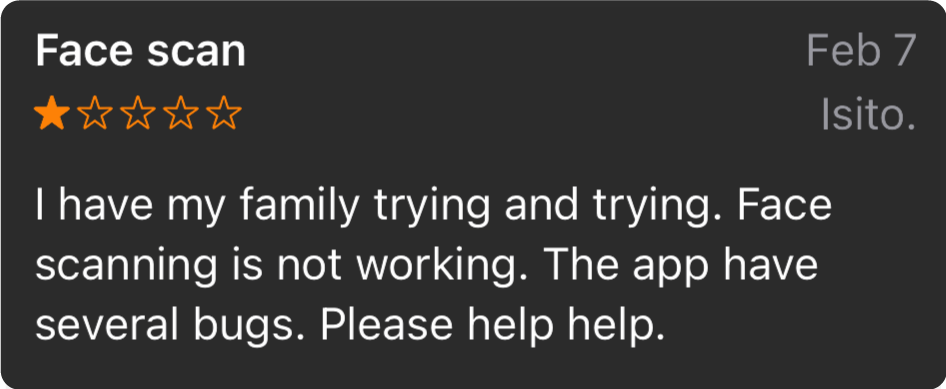

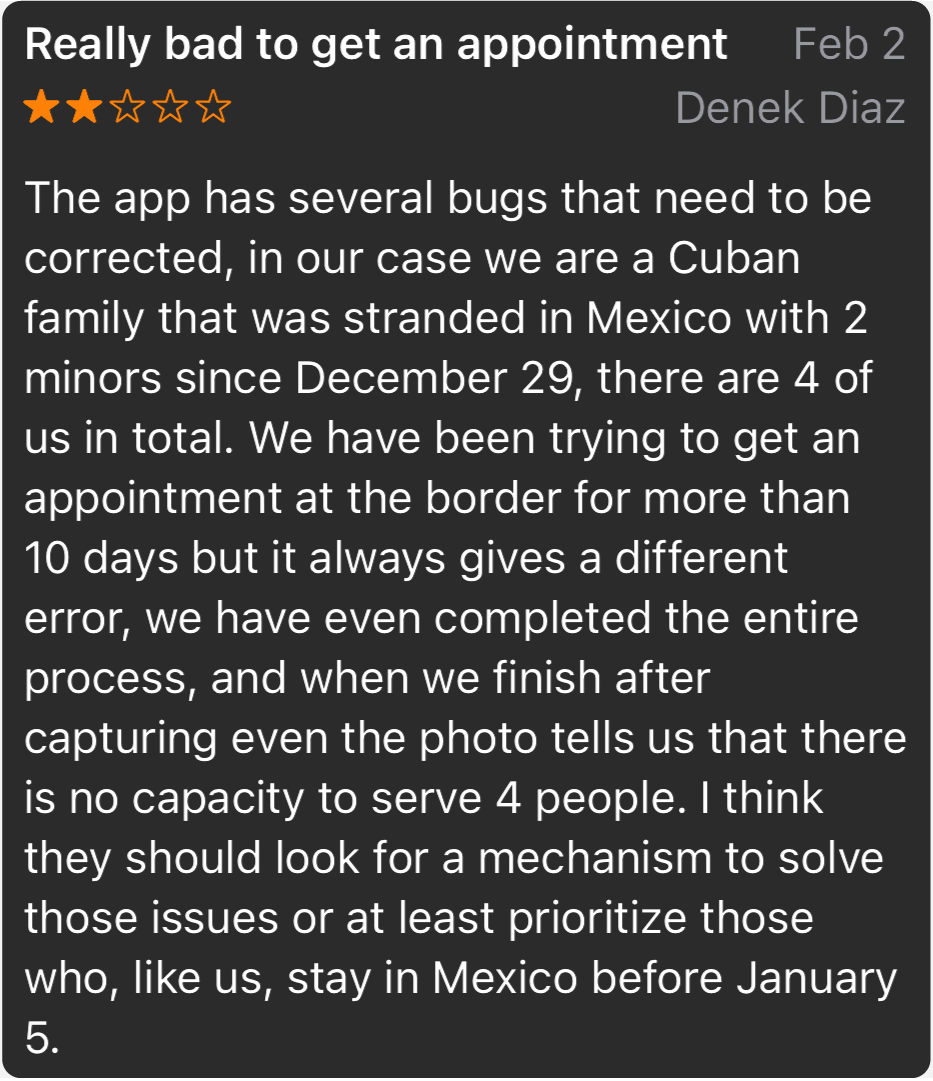

And that’s nothing to say of the technology itself, which migrants and human rights groups working along the border say is almost irredeemably flawed. Among its issues are a facial matching algorithm that has trouble identifying darker skin tones and a glitchy interface that routinely freezes and crashes when people try to log in. For people like Kat, it is nearly impossible to secure one of the limited number of appointments that the government makes available each day.

CBP One success stories are few and far between. Orta recalled a man who dropped to the ground and let out a shriek when he made an appointment. A group of migrants embraced him as he wept. “That’s how rare it is,” she said. “People fall to their knees and hold each other and cry because no one has ever gotten an appointment before.”

The week after Title 42 ended, I checked in with Orta. In the lead-up to the program’s expiration, the Biden administration announced that immigration officials would make 1,000 appointments available on CBP One each day and would lengthen the window of time for asylum seekers to try to book them. But Orta said the changes did not resolve the app’s structural flaws. CBP One was still crashing and freezing when people tried to log in. Moreover, the number of appointments immigration authorities offer daily — 1,000 across the southern border — is not nearly enough to accommodate the demand triggered by the expiration of Title 42.

“It’s still a lottery,” she sighed. “There’s nowhere in the app to say, ‘Hey, I have been sexually abused, please put me first.’ It’s just your name.”

Back in the spring, as Kat struggled with the app day after day, Orta and her colleague decided to begin documenting her attempts. She shared one of those videos with me, taken in early March. Kat — slight, in a black T-shirt — sat in a chair in Reynosa, fidgeting as she waited for CBP One’s appointment-scheduling window to go live. When it did, she let out a nervous sigh, opened the app and clicked on a button to schedule a meeting. The app processed the request for several seconds and then sent her to a new page telling her she didn’t get an appointment. When Kat clicked the schedule button again, her app screen froze. She tried again and again, but nothing worked. She repeated some version of this process every day for a week, while her attorneys filmed. But it was no use — she never succeeded. “It was impossible for her,” Orta said.

Kat is far from the only asylum seeker who has documented CBP One’s shortcomings like this. Scores of asylum seekers attempting to secure an appointment have shared their struggles with the technology in Apple’s App Store. Imagine the most frustrating smartphone issue you’ve ever encountered and then add running for your life to the mix. In the App Store, CBP One’s page features dozens of desperate reviews and pleas for technological assistance from migrants stranded in Mexico.

“This is just torture,” one person wrote. “My girlfriend has been trying to take her picture and scan her passport for 48 hours straight out of desperation. She is hiding in a town where she has no family out of fear. Please help!” Another shared: “If I could give negative stars I would. My family are trying to flee violence in their country and this app and the photo section are all that’s standing in the way. This is ridiculous and devastating.”

The app, someone else commented, “infringes on human rights. A person in this situation loses to a mechanical machine!”

In Kat’s case, her lawyers tried other routes. They enlisted an academic who studies cartels’ treatment of women along the border to submit an expert declaration in her case. Finally, after more than six weeks of trying and failing to secure an appointment, Kat was granted an exception and allowed to enter the U.S. to pursue her asylum claim without scheduling an appointment on CBP One. Kat and her son are now safely inside the country and staying with a family friend.

Kat was fortunate to have a lawyer like Orta working on her case. But most people aren’t so lucky. For them, it will be CBP One that determines their fates.

Biden administration officials claim that the tools behind their digitized immigration enforcement strategy are more humane, economical and effective than their physical counterparts. But critics say that they are just jail cells and walls in digital form.

Cynthia Galaz, a policy expert with the immigrant rights group Freedom for Immigrants, told me that U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement, which oversees Alternatives to Detention, “is taking a very intentional turn to technology to optimize the tracking of communities. It’s really seen as a way to be more humane. But it’s not a solution.”

Galaz argues that the government’s high-tech enforcement strategy violates the privacy rights of hundreds of thousands of migrants and their broader communities while also damaging their mental health. “The inhumanity of the system remains,” she said.

Alternatives to Detention launched in 2004 but has seen exponential growth under the Biden administration. There are now more than 250,000 migrants enrolled in the digital surveillance system, a jump from fewer than 90,000 people enrolled when Biden took office in January 2021. According to ICE statistics, the vast majority of them are being monitored through SmartLINK, the mobile phone app that people are required to download and use for periodic check-ins with the immigration agency. Migrants enrolled in this system face a long road to a life without surveillance, spending an average of 446 days in the program.

During check-ins, migrants enrolled in the program must upload a photo of themselves, which is then matched to an existing picture taken during their program enrollment using facial recognition software. The app also captures the GPS data of participants during check-ins to confirm their location.

The government’s increasing reliance on SmartLINK has shifted the geography of its embodied surveillance program from the ankle to the face. The widespread use of this facial recognition app is expanding the boundaries of ICE’s digital monitoring system, this time from a wearable device to something that is less visible but ever-more ubiquitous.

Proponents at the Department of Homeland Security say that placing migrants under electronic monitoring is preferable to putting them in detention centers as they pursue their immigration cases in court. But digitization raises a whole new set of concerns. Alongside the psychological effects of technical monitoring regimes, privacy experts have expressed concern about how authorities handle and store the data that these systems collect about migrants.

SmartLINK collects wide swaths of data from participants during their check-ins, including location data, photos and videos taken through the app, audio files and voice samples. An FAQ on ICE’s website says the agency only collects participants’ GPS tracking data during the time of their check-ins, but also acknowledges that it has the technical ability to gather location data in real-time from participants who are given an agency-issued smartphone to use for the program — a key concern for migrants enrolled in the program and privacy experts. The agency also acknowledges that it has access to enrollees’ historical location data, which it could theoretically use to determine where a participant lives, works and socializes. Finally, privacy experts worry that the data collected by the agency through the program could be stored and shared with other databases operated by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, which oversees ICE — a risk the agency recently conceded in its first-ever analysis of the program.

Hannah Lucal, a technology fellow with the immigrant rights legal firm Just Futures Law, which focuses on the intersection of immigration and technology, has studied the privacy risks of Alternatives to Detention at length. She told me she sees the program’s wide-ranging surveillance as “part of a broader agenda by the state to control immigrant communities and to limit people’s autonomy over their futures and their own bodies.”

And the program’s continuous electronic monitoring has left some migrants with physical and psychological damage. The ankle monitors, Lucal said, “cause trauma for people even after they’ve been removed. They give people headaches and sores on their legs. It can be really difficult to bathe, it can be really difficult to walk, and there’s a tremendous stigma around them.” Meanwhile, migrants using SmartLINK have expressed to Lucal fears of being constantly watched and listened to.

“People talked about having nightmares and losing sleep over just the anxiety that this technology, which is super glitchy, may be used to justify further punishment,” she explained. “People are really living with this constant fear that the technology is going to be used by ICE to retaliate against them.”

Alberto was busy at work when he missed two calls from his Alternatives to Detention supervisor. The 27-year-old asylum seeker had been under ICE’s e-monitoring system since he arrived in the U.S. in 2019. He was first given an ankle monitor but eventually transitioned over to the agency’s mobile check-in app, SmartLINK. Once a week, Alberto was required to send a photo of himself and his GPS location to the person overseeing his case. On those days, Alberto, who works with heavy and loud machinery, would stay home from his job to ensure everything went smoothly.

But one day this past spring, Alberto’s supervisor called him before his normal check-in time, while he was still at work. He didn’t hear the first two calls over the buzz of the room’s machinery. When things quieted down enough for Alberto to see another call coming in, he picked up. Fuming, Alberto’s supervisor ordered him to come to the program’s office the following day.

“I told her, ‘Ma’am I have to work, I have three kids, I have to support them,’” he told me in Spanish.

“That doesn’t matter to me,” the case worker replied.

When Alberto showed up the next day, as instructed, he was told by his Alternatives to Detention supervisor that he had more than a dozen violations for missing calls and appointments — which he disputes — and he was placed on the ankle monitor once again.

The monitor is bulky and uncomfortable, Alberto explained. In the summer heat, when shorts are in season, Alberto worries that people who catch a glimpse of the device will think he’s a criminal.

Loren Elliot / AFP via Getty Images.

“People look at you when they see it,” he said, “they think that we’re bad.” The situation has worn on him. “It’s ugly to wear the monitor,” he told me. And it weighs even more heavily on him now that he is not sure when it will come off.

Over the past year, I’ve interviewed dozens of people with extensive knowledge of Alternatives to Detention, including immigration attorneys, researchers, scholars and migrants who are, or were, enrolled in the program. Those discussions, as well as an emerging body of research, suggest that Alberto’s reaction to the electronic monitoring he was exposed to is not uncommon.

In 2021, the Cardozo School of Law published the most comprehensive study on the program’s effects on participants’ well-being, surveying roughly 150 migrants who wear ankle monitors. Ninety percent of people told researchers that the device harmed their mental and physical health, causing inflammation, anxiety, pain, electric shocks, sleep deprivation and depression. Twelve percent of respondents said the ankle monitor resulted in thoughts of suicide, and 40% told researchers they believed that exposure to the device left them with life-long psychological scars.

Berto Hernandez, who had to wear an ankle monitor for nearly two years, described the device as “torturous.” “Besides the damage they do to your ankles, to your skin, there’s this other implication of the damage it does to your mental health,” Hernandez said.

Hernandez, who uses they/them pronouns, immigrated with their parents to the U.S. from Mexico at age 10. In 2019, when they were 30 years old, they were detained by immigration officers and enrolled in Alternatives to Detention as their deportation case proceeded.

Hernandez was in college while they had to wear the monitor and told me a story about a time they drove to a student retreat with a peer a few hours away from their home in Los Angeles. All of a sudden, the ankle monitor started beeping loudly — an automatic response when it exits the geographic range determined by immigration authorities.

“I had a full panic attack,” Hernandez told me. “I started crying.” Although they had alerted their case manager that they would be out of town, Hernandez says their supervisor must have forgotten to adjust their location radius. After the incident, Hernandez had a physical reaction every time the device made noise.

Subscribe to our Authoritarian Tech newsletter

From biometrics to surveillance — when people in power abuse technology, the rest of us suffer. Written by Ellery Biddle.

“Whenever the monitor beeped, I would get full on panic attacks,” they explained. “Shaking, crying. I was fearful that they were going to come for me.” Hernandez thinks the level of fear and lack of control is part of the program’s objectives. “They want you to feel surveilled, watched, afraid,” they said. “They want to exert power over you.”

Hernandez was finally taken off of the ankle monitor in 2021, after appealing to their case manager about bruises the device left on their ankles. Hernandez was briefly allowed to do check-ins by phone but will soon be placed on SmartLINK. They don’t buy the government’s message that these technologies are more humane than incarceration.

“This is just another form of detention,” they told me. “These Alternatives to Detention exert the same power dynamics, the same violence. They actually perpetrate them even more. Because now you’re on the outside. You have semi-freedom, but you can’t really do anything. If you have an invisible fence around you, are you really free?”

Once on SmartLINK, Hernandez will join the 12,700-plus immigrants in the Los Angeles area who are monitored through the facial recognition app. Harlingen, Texas, has more than double that amount, with more than 30,600 placed under electronic monitoring — more than anywhere else in the country. This effectively creates pockets of surveillance in cities and neighborhoods where significant numbers of migrants are being watched through ICE’s e-monitoring program, once again extending the geography of the border beyond its physical range.

“The implication of that is you never really arrive and you never really leave the border,” Austin Kocher, a Syracuse University researcher focusing on U.S. immigration enforcement who has studied the evolving geography of the border, told me. Kocher says these highly concentrated areas of migrant surveillance are known as “digital enclaves”: places where technology creates boundaries that are often invisible to the naked eye but hyperpresent to those who are subjected to the technology’s demands.

“It’s not like the borders are like the racial impacts of building freeways through our cities, and things like that,” he noted. “They’re kind of invisible borders.”

Administering all of this technology is expensive. The program’s three monitoring devices cost ICE $224,481 daily to operate, according to agency data.

On that end, there is one clear beneficiary to these expansions. B.I. Incorporated, which started out as a cattle-tracking company before pivoting to prison technology, is the government’s only Alternatives to Detention contractor. It currently operates the program’s technology and manages the system through a $2.2 billion contract with ICE, which is slated to expire in 2025. B.I. is a subsidiary of the GEO Group, a private prison company that operates more than a dozen for-profit immigrant detention centers nationwide on behalf of ICE. GEO Group earned nearly 30% of its total revenue from ICE detention contracts in 2019 and 2020, according to an analysis by the American Civil Liberties Union. Critics like Jacinta Gonzalez, an organizer with the immigrant’s rights group Mijente, say this entire system is corrupted by profit motives — a money-making scheme for the companies managing the detention system that sets up financial incentives to put people behind physical and digital bars.

And B.I. may soon add another option to its toolkit. In April, ICE officials announced that they are pilot testing a facial recognition smartwatch to potentially fold into the e-monitoring system — an admission that came just weeks after the agency released its first-ever analysis of the program’s privacy risks. In ICE’s announcement of the smartwatch rollout, the agency said the device is similar to a consumer smartwatch but less “obtrusive” than other monitoring systems for migrants placed on them.

Austin Kocher, the immigration enforcement researcher, said that touting technologies like the smartwatch and the phone app as “more efficient” and less invasive than previous incarnations, like the ankle monitors, is tantamount to “techwashing” — a narrative tactic to gain support and limit criticism for whatever shiny new tech tool the authorities roll out.

“With every new technology, they move the yardstick and say, ‘Oh, this is justified because ankle monitors aren’t so great after all,’” Kocher remarked. For people like Kocher, following the process can feel like an endless loop. First, the government detained migrants. Then it began to release them with ankle monitors, arguing that surveillance was kinder than imprisonment. Then it swapped the monitors for facial recognition, arguing that a smartphone is kinder than a bulky ankle bracelet. Each time, the people in charge say that the current system is more humane than what it had in place last time. But it’s hard to know where, or how, it will ever end — and who else will be dragged into the government’s surveillance web in the meantime.

For people like Alberto, there is no clear end in sight. He doesn’t know when the monitor will come off. But he knows it won’t be removed until his supervisor gives the okay. It can’t malfunction if he wants to avoid getting in trouble again. And he can see his daughter is paying attention.

Recently, she noticed the monitor and asked him what it was. Alberto tried to keep it light. “It’s a watch,” he told her, “but I wear it on my ankle.” She asked him if she could have one too.

“No,” he replied. “This one is only for adults.”

The story you just read is a small piece of a complex and an ever-changing storyline that Coda covers relentlessly and with singular focus. But we can’t do it without your help. Show your support for journalism that stays on the story by becoming a member today. Coda Story is a 501(c)3 U.S. non-profit. Your contribution to Coda Story is tax deductible.

The Big Idea

Shifting Borders

-

When your body becomes the border

feature Erica Hellerstein

-

India and China draw a line in the snow

feature Shougat Dasgupta

-

How an EU-funded agency is working to keep migrants from reaching Europe

feature Zach Campbell and Lorenzo D'Agostino

-

Turkey uses journalists to silence critics in exile

feature Frankie Vetch