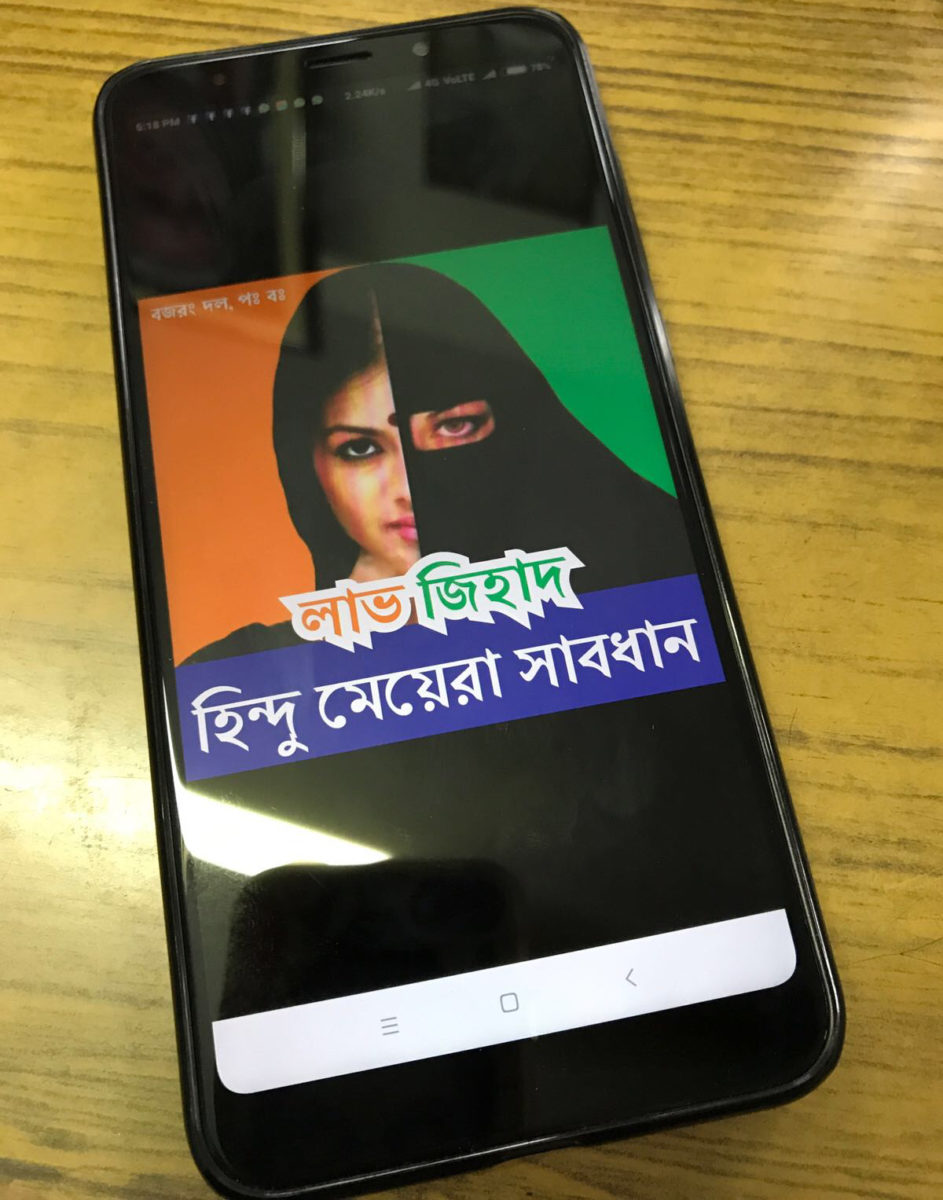

Avishek Das/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

When India’s right wing comes for interfaith marriage

In India, the last two months of 2022 were dominated by lurid media coverage of the deaths of two women. One of the women, Shraddha Walkar, was murdered by her boyfriend in Delhi. Her body had allegedly been cut up into 35 pieces, stored in a refrigerator and gradually disposed of in a forest. Walkar’s father reported her missing after her friends said her cell phone had been switched off for months. She had been murdered in May. Her boyfriend was arrested in November and is currently in judicial custody.

The second woman, Tunisha Sharma, a 20-year-old actor, allegedly hung herself on December 24 on the set of a TV show that she was working on with her boyfriend. They had apparently broken up shortly before her death. After Sharma’s death, her boyfriend was arrested for “abetment to suicide.”

What links the otherwise unconnected deaths of these two young women is that they were Hindu and their boyfriends were Muslim. Predictably, both cases were reported in the mainstream Indian media, particularly on television, as examples of “love jihad” — a right-wing conspiracy theory alleging that vulnerable Hindu women are being groomed by Muslim men and converted to Islam.

Asif Khan, a resident of Dindori, in the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh, married Sakshi Sahu in April. They were in their early 20s. As the news spread through their village of a Muslim man marrying a Hindu woman, local Hindutva (or Hindu nationalist) groups mobilized to “rescue” Sakshi.

The law was on the side of the vigilantes. The police booked Asif for wrongful confinement and kidnapping, based on a complaint by Sakshi’s brother. A local BJP unit blocked a nearby highway to protest the marriage and the district administration demolished Asif’s family home and three shops they owned.

Still, the couple refused to break up, leaving their village to live a quieter married life elsewhere. But news of Walkar’s murder, and the associated national talk of love jihad, reintroduced stresses and fears into their marriage. “We have been reassuring Sakshi that she doesn’t need to be afraid,” Asif’s father, Halim Khan, told me. “But she is scared.” Asif told me that he had told Sakshi “society would never accept [their] relationship” but that she had said she would “throw herself in front of a train” if they broke up because of their religion.

But the anger evident in the media coverage of Walkar’s death shook the couple. Asif told Sakshi that “she is not a captive, that she can go back to her parents if she wants.”

According to Charu Gupta, a history professor at Delhi University, love jihad “produces a master narrative of Muslim male aggression and Hindu woman’s seizure.” This, she wrote, is “critically linked to the fictive demographic fear of Hindus being outnumbered by others, which is central to Hindutva politics,” and makes it possible for a still overwhelming majority that controls all the levers of power to “portray itself as an ‘endangered’ minority.”

Several politicians, particularly from the BJP, the party that controls India’s federal government, have referred to the deaths of Walkar and Sharma in terms of love jihad. In Karnataka — the Indian state that contains Bengaluru, a city that is, by some estimates, second only to Silicon Valley as a global hub for tech — a BJP member of parliament began the new year by telling party workers that, when campaigning for local elections scheduled in the spring, they should not “speak about minor issues like roads and sewage.” Instead, they should impress on voters that “if you are worried about your children’s future and if you want to stop love jihad, then we need BJP… To get rid of love jihad, we need BJP.”

Just last month, Karnataka’s home minister told reporters that he had received a petition from Hindutva groups demanding that a special task force be formed to investigate love jihad. He added that in his view, the state’s anti-conversion laws were sufficient to deter and deal with cases of love jihad. Karnataka, governed by the BJP, has so far resisted joining other BJP-governed states, such as Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh, in specifically legislating to make interfaith marriage more difficult.

In Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state with over 200 million people, the chief minister, a Hindu monk notorious for hate speech, told a crowd in a campaign speech that he would “protect the honor and dignity of women” from love jihad “at any cost.” In February 2021, Uttar Pradesh introduced a law that criminalized religious conversion “through marriage, deceit, coercion, or enticement.” Those found guilty can be imprisoned for up to a decade.

And in Madhya Pradesh, which sprawls across the center of India, the chief minister referred to Walkar’s murder in December, at an event to celebrate a local 19th-century freedom fighter. The hero was a tribal, a term used in India to refer to ethnic minorities, officially designated in the Indian constitution as Scheduled Tribes, who remain some of the most economically underprivileged people in the country. “I will not allow this game of love jihad to continue,” the chief minister said. “Someone cheats our daughters in the name of love, marries them, and cuts them into 35 pieces. Such acts will not be allowed in Madhya Pradesh.” This, even though Walkar was not murdered in the state and was not a tribal.

Statements such as these, made by powerful politicians, have put even more pressure on the few people brave enough to enter into interfaith marriages in India. Even before the right-wing, Hindu supremacist bogeyman of love jihad became widespread, interfaith relationships in India were rare. Now they are dangerous.

Just over 2% of marriages in India are interfaith. A Pew Research Center report in 2021 indicated that 99% of Hindus in India said they were married to someone from their own religious background, as did 98% of Muslims, 97% of Sikhs and Buddhists and 95% of Christians. These statistics underscore the ideological impetus behind the legislation in BJP-ruled states that seek to tackle religious conversion, and specifically love jihad, when the phenomenon clearly appears to be a figment of the imagination.

In Uttar Pradesh, where you can be imprisoned if the authorities deem your marriage to be one in which the primary motivation was religious conversion, Rashid Khan, a Muslim man, married Pinki, a Hindu woman. They married in 2020, the year that the state’s draconian anti-conversion law was formulated though not yet passed. Pinki told me she knew their future was fraught with danger but she went ahead and asked for Rashid’s phone number anyway.

Both Pinki and Rashid worked in Dehradun, a city nestled in the picturesque foothills of the Himalayas, and they grew close over long conversations and stolen moments between shifts. Three years later, Rashid said he wanted to marry her, and he was willing to marry her according to Hindu custom and ritual. Pinki said she had long been drawn to Islam and wanted to have a Muslim wedding and to convert. On July 24, their marriage was solemnized in a nikah in a Dehradun mosque. Pinki changed her name to Muskan.

Initially, Muskan tried to get her family to accept their marriage, but her mother beat her and threw her out of the house. Still, the early months of their marriage were happy and soon Muskan was pregnant with their first child.

When the couple decided to get their marriage officially recorded in a court in Moradabad, in Uttar Pradesh, where Rashid was from, their petition was noticed by a local unit of the Bajrang Dal — a group of Hindutva militants which is part of the broader Sangh Parivar, the Hindutva “family” that includes the BJP. The couple suspects that their lawyer tipped off the Bajrang Dal. Rashid and Muskan were attacked on their way to the courthouse.

The mob beat up Rashid and his brother and took them to the police station. Meanwhile, Muskan, who was in the fourth month of her first pregnancy, was severely beaten and dumped outside a government-run shelter for women and children. “I was in trauma and extreme pain. I thought I would never see Rashid again,” Muskan told me, adding that there were other women who were romantically involved with Muslim men being held at the shelter. “We were all tortured,” she alleged. “Made to work, cooking and cleaning continuously. I spent the days crying and in pain.”

Muskan was eventually moved to a hospital, where she says she was injected by a doctor with undisclosed medicines. Shortly after, she suffered a miscarriage and was discharged the next day.

When Rashid was brought to court, Muskan said she loved him and that she had married him of her own free will. Her testimony convinced the court to release Rashid. The couple moved back to Dehradun to restart their lives in a single room. “This is the safest place we could find,” she told me. They have had a child since the miscarriage, and Muskan is breastfeeding her on the double bed that takes up most of the space in the room. Rashid, and his sister with her husband and son, were also sitting on the same bed. In another corner, a gas stove perched on a table served as the kitchen.

Since Narendra Modi swept into office in 2014 and was reelected with an even stronger mandate in 2019, almost every Muslim action is freighted with the word “jihad.” The mainstream Indian media have used this shorthand with relish. On March 11, 2020, Sudhir Chaudhary, a prominent and popular Indian journalist, presented his viewers with a chart outlining the various kinds of jihad to which India’s Hindus were subject. He talked about “hard” jihad and “soft” jihad, about the jihad being waged by the media, about the jihad being waged on history, on land rights, on the Indian economy, on affairs of the heart. The media even attempted to pin the spread of Covid in India to a single superspreader event connected to an Islamic conclave in a Delhi neighborhood, labeling it “corona jihad.”

Another prominent Indian television journalist described an attempt by Muslims to “infiltrate” the civil services by passing a nationwide exam as the “UPSC jihad.” Muslims are drastically underrepresented in India’s civil services, and the number is dwindling, with only 3% qualifying to join the services in 2021, even though Muslims make up an estimated 14% of the population. Meanwhile, the 2021 National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) report shows that Muslims comprise more than 30% of India’s prison population.

Last year, Gregory Stanton, the founder of Genocide Watch, said during a U.S congressional briefing that Modi was an “extremist who has taken over the government.” Stanton, a credible and highly respected scholar, said: “We are warning that genocide could very well happen in India.”

Aasif Mujtaba, the founder of a nonprofit organization, Miles2Smile, told me that Muslims had already been effectively demeaned in India and were now being openly persecuted. He said that the word “jihad” had been weaponized, that it had been used to create an “us versus them narrative, in which the ‘them’ are Muslims who are considered to be lesser humans.” They are trying, now, Mujtaba added, to “delegitimize Muslims as citizens of the land.”

He is, in part, referring to the controversial Citizenship (Amendment) Act which led to weeks of protests until Covid-related lockdowns forced protesters off the street. The United Nations described the act — which offers a path to citizenship to everyone except Muslims who fled to India from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh before 2014 because they were persecuted for their religious beliefs — as “fundamentally discriminatory in nature.” But Mujtaba is also referring to a general atmosphere in which drastic, even illegal measures can be taken to punish Muslims for alleged crimes, including bulldozing their homes, breaking up their relationships and boycotting or shutting down their businesses. In October, Meenakshi Ganguly, the South Asia director at Human Rights Watch, said: “The authorities in several Indian states are carrying out violence against Muslims as a kind of summary punishment… [they] are sending a message to the public that Muslims can be discriminated against and attacked.”

But Muskan, who told a court in Uttar Pradesh of her love for Rashid, remains defiant. “Even though they say that Muslim men manipulate Hindu girls,” she told me, “it was me who initiated our relationship. I made a choice. They might call it jihad but people like us won’t stop loving each other.”

The story you just read is a small piece of a complex and an ever-changing storyline that Coda covers relentlessly and with singular focus. But we can’t do it without your help. Show your support for journalism that stays on the story by becoming a member today. Coda Story is a 501(c)3 U.S. non-profit. Your contribution to Coda Story is tax deductible.