J. Countess/Getty Images

How TikTok influencers exploit ethnic divisions in Ethiopia

When Ethiopians took to the streets in February in reaction to a highly politicized rift within the country’s Orthodox Tewahedo Church, government authorities temporarily blocked social media platforms. On the outside, it may have seemed like just another blunt force measure by an authoritarian state trying to quell social unrest. But the move was more keenly calculated than that — the rhetoric of social media influencers was having an outsized impact on how Ethiopians, both in the country and in Ethiopia’s politically influential diaspora, perceived what was happening. Similar to other moments of intense social conflict amid Ethiopia’s civil war, TikTok became a ground zero for much of the conflict playing out online.

In early February, three archbishops of the Orthodox Tewahedo Church — one of the oldest churches in Africa that dates back to the 4th century — accused fellow church leaders of discriminating against the Oromo people, who constitute the largest ethnic group in Ethiopia’s population of 120 million. While church members come from a diverse array of ethnic backgrounds, worship services are predominantly conducted in the liturgical language of Ge’ez and in Amharic, which is a language primarily spoken by the Amhara people. Amharic is the dominant language of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital, and the working language of the federal government. This linguistic predilection underlines the cultural clout of Amharic.

After the three archbishops — all of Oromo lineage — made their allegations of discrimination public, they were excommunicated by church authorities. They then declared their plans to form a breakaway synod, triggering an instant public outcry. The cleavages underlying Ethiopia’s civil conflict bubbled to the surface and devolved into violent skirmishes, resulting in a combined total of 30 fatalities in the southern Ethiopian town of Shashemene and in Addis Ababa.

But what was a serious political crisis for the church and for the country amounted to a prime opportunity for TikTok influencers seeking to spread their messages and turn a profit along the way.

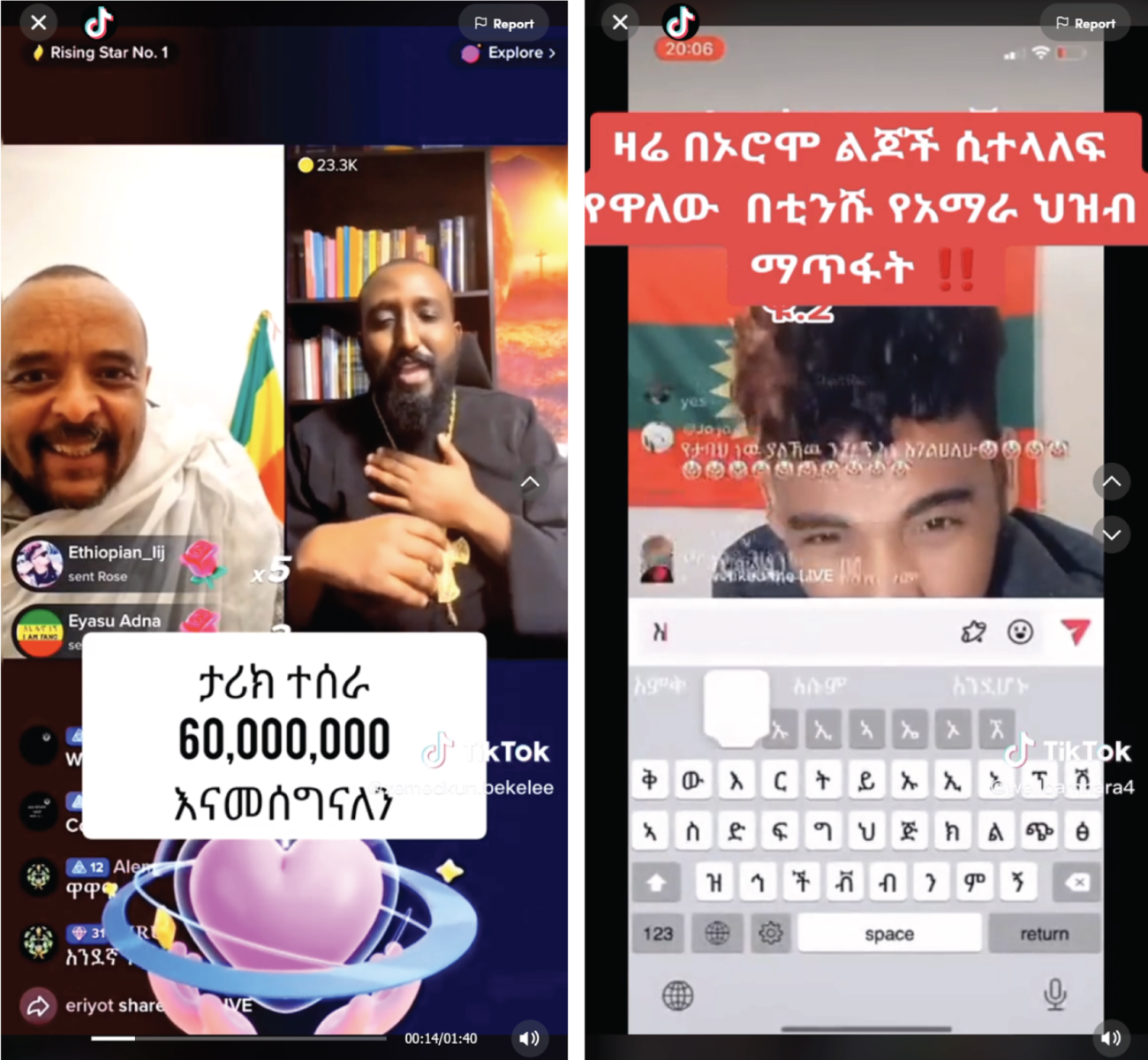

A quick scroll through live sessions on TikTok reveals heated political discussions in Amharic, Oromo and Tigrinya, in which participants exchange barbs and strategize on how to confront their adversaries. Zemedkun Bekele is prominent among them. A self-proclaimed defender of the Orthodox Tewahedo Church, he is known for his forceful, admonitory videos that are often over an hour long. Bekele began broadcasting threats against the breakaway synod, claiming to have video evidence that its leaders had engaged in homosexual activity and threatening to release the tape to the public. Accusations like this resonate deeply in a nation steeped in conservatism, where homosexuality is viewed with considerable disdain.

A known social media influencer who had already been banned from both Facebook and YouTube in 2020 for violating their policies on hate speech and the promotion of violence, Bekele re-established himself on TikTok in February 2023, just in time to jump into the fray. Since then, he has amassed a dedicated audience of more than 203,000 TikTok followers, most of whom appear to be members of the Amhara ethnic group and followers of the Orthodox Tewahedo Church.

In the midst of the crisis, Bekele also launched attacks against a senior church teacher, Daniel Kibret, who has become a staunch ally of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed. Drawing on the fact that the prime minister comes from a mixed religious background (his father is Muslim and his mother is Christian), Bekele made unfounded claims that Kibret had secretly converted to Islam.

In a video with more than 19,000 views, Bekele maintained that he would not relent. “We will not back down without making sure the Ethiopian Orthodox Church is as big as the country itself. We will not back down without toppling Abiy Ahmed,” he said. “We will not back down without hanging Daniel Kibret upside down.” The video was posted on February 4, the same day that the three bishops declared their intentions to secede from the Church.

Another account called TegOromo also saw swift growth surrounding the church controversy. TegOromo has a passionate following and is on the opposite side of the conflict from Bekele. The person who runs the account has expressed support for the Oromo religious leaders who sought to establish the independent synod. The account’s moniker fuses the first three letters of “Tegaru” with “Oromo” — a calculated move to represent harmony between the Tigrayan and Oromo ethnic groups.

With more than 60,000 followers, TegOromo’s account is marked by overt threats, inflammatory language and aggressive rhetoric. One TikTok video urged supporters to “chop the Amharas like an onion.” This video was later removed from the platform, but copies of it remain accessible. In a live session, a TegOromo follower called on Oromo people to “kill all Amharas” and even specified that children should not be spared. TegOromo cheered him on, urging other followers to answer the call and take up arms.

Despite the controversial nature of TegOromo’s content, the influencer’s popularity suggests a burgeoning trend. Republishing his material or circulating incisive and satirical clips featuring TegOromo has become a reliable strategy for Ethiopian content creators seeking higher engagement.

In another instance, the spotlight turned toward two emerging TikTok influencers, Dalacha and Betayoo, who garnered attention for their adept use of vitriol. In one video, Dalacha, who identifies as Oromo, launched a barrage of insults and sexual slurs at his rival TikToker, Maareg, who identifies as Amhara. The episode exemplified the depths to which Dalacha was willing to stoop in order to denigrate Maereg. Dalacha used language that reduced the Amhara community to mere cattle. It was intended only to amplify the prevailing animosity between the two ethnic groups.

In another video, Betayoo, who consistently identifies as Amhara, used similarly troubling language, employing both sexual and ethnic slurs. She directed her insults toward a rival TikToker who identifies as Tigrayan and who has publicly expressed disdain for the Amhara community. Betayoo’s actions escalated beyond targeting an individual. She proceeded to insult the entire Tigrayan community, expressing a desire for their eradication.

The videos I reference above also all contain clear violations of TikTok’s terms of service, yet they remain on the platform. TikTok’s Community Guidelines strictly prohibit hate speech or hateful behavior and promise to remove such material from their platform. Accounts and/or users that engage in severe or multiple violations of hate speech policies are promptly banned from the platform. Despite these guidelines, plenty of Ethiopians who have exhibited hateful behavior remain active on the platform and continue to produce content for significant numbers of followers.

When I approached TikTok staff members to alert them about the videos and ask them to comment for this piece, they did not respond. It is difficult to definitively prove that this kind of discourse directly contributes to violence on the ground. But it is clear that discussions of political violence and religious conflicts on TikTok often result in the spread of misinformation and amplify interethnic hatred. Clips containing these influencers’ offensive remarks have also seeped onto other platforms, such as YouTube and Facebook, where reposting or critiquing such content has become a low-effort method for content creators to gain engagement.

Given the sheer volume of such live streams, TikTok’s moderation team may be overwhelmed, struggling to monitor these discussions and remove inappropriate content. It is also worth noting that all of these accounts are run primarily in Amharic, Oromo or Tigrinya, languages that are spoken by millions of Ethiopians in and outside of the country but that have historically been underrepresented on major social media platforms. TikTok does not publicly disclose how many staff members or content moderators it employs for reviewing content in these languages.

All this engagement is not driven purely by political vitriol — it is also a pursuit of profit. The TikTok LIVE feature has seen a swift uptick in popularity among Ethiopian users, catalyzing an emergence of politically-minded influencers who reap economic rewards through virtual gifts. These gifts can be converted into TikTok “diamonds,” which are in turn redeemable for actual cash.

Crafting politically-charged clickbait, designed to fan the flames of ethnic and religious discord, is emerging as a common tactic for financial gain. It has had especially strong uptake among individuals in the Ethiopian diaspora. Many of the most impactful Ethiopian TikTok figures are actually located in Western nations. Zemedkun Bekele, for instance, lives in Germany.

Amid the ongoing crisis, Bekele proudly claimed to have received one of the most sought-after TikTok LIVE gifts — the lion, which translates to a little over $400 in real-world currency. He has prominently featured a video on his profile displaying a virtual lion roaring at the screen, serving as both a symbol of his influence and a testament to the economic gains that one can reap through this kind of engagement on TikTok.

In a 2021 essay, former New York Times media critic Ben Smith showed how TikTok’s algorithmic recommendation framework has helped to intensify cultural, linguistic and ideological divides among its global user base. The unfolding situation in Ethiopia could serve as a case study for Smith’s argument. With the videos I described — in addition to hundreds of others — the platform’s content dissemination strategy appears to inadvertently encourage distinct factions to isolate themselves and push each other to commit hate speech and even physical violence.

The rise of these online strongholds poses significant challenges to promoting inclusive, cross-cultural understanding that TikTok claims to want to foster. Users now risk becoming trapped in ideological echo chambers, detached from diverse perspectives and viewpoints, and increasingly vulnerable to politically-motivated disinformation.

At the core of the issue lies the question of accountability. What obligation does TikTok, and by extension other social media platforms, have to curtail the spread of divisive content, particularly when it is financially incentivized? And moreover, could the pursuit of profit from politically-charged content inadvertently pave the way for more extreme or hazardous content, potentially triggering threats of violence in real life?

In the end, for onlookers familiar with Ethiopian culture and politics, it is clear that the platforms that invite us to share our lives online are failing to mediate the complexities of the world they seek to engage with.

The story you just read is a small piece of a complex and an ever-changing storyline that Coda covers relentlessly and with singular focus. But we can’t do it without your help. Show your support for journalism that stays on the story by becoming a member today. Coda Story is a 501(c)3 U.S. non-profit. Your contribution to Coda Story is tax deductible.